Your kidneys are like filters. Your brain is like a computer. Your digestive system is like a tube. Your hands are controlled a bit like a marionette. These comparisons exist in part because doctors and scientists are desperate to find ways to visualize our bodies, in search of aids to understanding—with the bonus that it’s not quite as visceral as the real thing.

All of these are useful, but one, I’ve discovered, is missing. Our bodies are like tubes or levers or computers, but they are, above all things, like bags. Bags that are stuffed in other bags, stuffed in still more bags. Our bodies are nesting bag situations like the used bags stuffed under your kitchen sink, with the added bonus of thumbs and anxiety. The analogy gives me clarity—when I have trouble understanding anatomy, I look for the bag. It gives me context—figuring out how to replicate or get inside our various bags is a critical part of modern medicine. Finally, it gives me comfort. Life isn’t that complex after all. It’s just a series of bags, getting more and more fancy and specialized.

If this sounds like the sort of thought that would come to someone sleep-deprived in the middle of the night, it is. I’ve been having difficulty sleeping since sometime in 2020, and I’m sure I’m not alone. Through trial, error, prescriptions and meditation apps, I have found the one thing that truly works for me—studying human anatomy. My insomnia led me on an exhaustive, 18-month-long search for boring, self-improving books, to be read by the light of a carefully dimmed lamp. After a perusal of classical literature, my eye fell on the holy grail. A brick of a tome, clocking in at 1,153 pages and a solid six pounds. Moore, Dalley and Agur’s Clinically Oriented Anatomy, the medical textbook of the Harvard Medical School’s “Human Functional Anatomy” course. Six months later, my book is as battered as any first-year medical student’s, and I am obsessed. I share the most fascinating anatomy facts on Bluesky, TikTok and Instagram, in a series I call Insomnia Anatomy Academy.

In the many hours waiting for sleep to finally set in, I’ve discovered all sorts of captivating tidbits—human anatomy can, paradoxically, really keep you up at night. Teeth are joints, and scientists are still learning about the ligaments that hold them in place. Some people have an extra set of ribs—coming from the last vertebrae in their neck. People who can breastfeed can have extra breast tissue that forms and releases milk—into their armpits. Every page offers a new weird fact that emphasizes our evolutionary history and our wild individual variability.

I can barely flip a page without running into a bag. Your skin? A many-layered sack, holding in all of your insides. Inside, the skin, bags abound. It’s perhaps easy to think of the stomach, which is a tube, closed off at the top and bottom by the esophageal and pyloric sphincters, as a bag. Or the bladder, a temporary storage bag for urine.

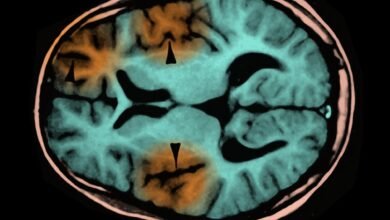

That’s not all. The heart gets not one but two bags: a tough outer fibrous pericardium and a serous pericardium, protecting the heart and fixing it firmly in place in our constantly moving thorax. The brain and spinal cord are triple-wrapped, with three layers of the meninges. These sacks physically protect our most delicate and essential bits. Inside, there’s another, different sack—a blood-brain barrier of linked cells that prevents most infections from touching the brain. Even the uterus is a bag—one that can be filled with a fetus. That fetus builds its own inner bag in conjunction with the parent, creating the placenta, layers of parental and fetal cells that protect and provide.

Your muscles even have bags. Groups of muscles that do the same thing, along with the nerves and vessels that keep them going, are bundled together into what are called fascial compartments. These bags are so tight they might be better described as flesh vacuum-packing cubes. These bags are more than just packaging. They reduce friction, and often merge into tendons. When one of these bags is injured or infected, the blood or infection will spread first inside the bag, allowing doctors to predict where it will go and intervene.

Nerves infest these bags as well, and so the network of bags might be sensory as well as storage. Scientists are still trying to figure out how manipulating our muscular packets could help with mobility or pain.

The bags don’t stop there. Joints are surrounded by joint capsules—tight, double-layered bags with thin layers of fluid that help our bones rub neatly against each other, allowing us to pivot without pain.

Bags don’t end with what we can see with the naked eye. Each cell on its own is a bag, a membrane separating its contents from the outside world. Within those cellular bags, like especially gooey matryoshka dolls, are organelles, minute bags separating out their own microchemistry. The organelles can each have a different pH and hold some molecules inside and keep others out.

Much like you may with the bags under your kitchen sink, cells even reuse and recycle some of their bags. Tiny bags called vesicles contain chemical messengers. Those bags dump their contents outside the cell, and merge with the larger bag of the cell itself, only to get pinched off and reused again when more packaging is required. Life itself can be drilled down to bags: the first cell wasn’t a cell until it was separated off from the outside world—until it had a bag.

Bags aren’t just a thought exercise for insomniacs—but something our medical knowledge grapples with daily. Scientists and doctors are still studying and often trying to replicate our many natural bags. Some are studying how to make synthetic vesicles, to release chemicals where and when we want them. Others are trying to build artificial placentas for premature infants. Some bags might be allies, while others might serve more as worthy adversaries. It’s a constant fight for new medicines to get past our determined brain bags to cure our mental ills.

Sitting with my anatomy text, and waiting patiently for sleep, I find my many bags both wonderous and comforting. The world can seem endlessly complex, full of the things we should have known, the things we did or didn’t do well enough. But human life, the physical stuff that makes us love and hate and judge and care? It’s just bags all the way down.

This is an opinion and analysis article, and the views expressed by the author or authors are not necessarily those of Scientific American.