DURHAM, N.C. (RNS) — Nine years ago this month, three Muslim students of Middle Eastern descent were having dinner in a condo development in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, when a neighbor banged on the door, barged in and shot and killed them, execution style.

The news of their murder and the subsequent conviction of their killer, an unemployed middle-aged white man with a small arsenal of firearms, shocked the world and shattered Chapel Hill’s idyllic image.

No one in the university town centered around the sprawling campus of the University of North Carolina, could remember another triple murder, much less one involving a religious minority.

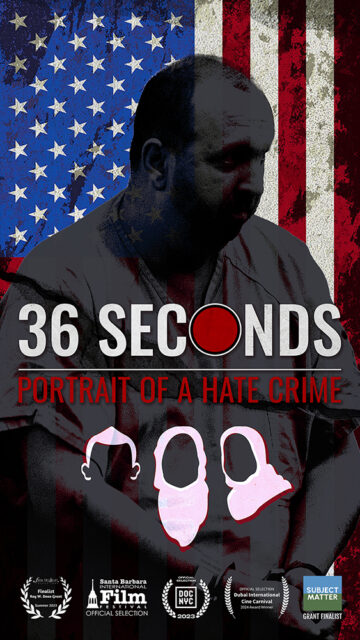

A new documentary now screening in North Carolina’s Triangle region and across the country in various film festivals and university campuses, tells the story of two wrongs: the horrific murders of three promising young people just starting their adult lives and the federal government’s unwillingness to prosecute the case as a religion-motivated hate crime.

“36 Seconds: Portrait of a Hate Crime” examines the heart-wrenching overnight pivot of the bereaved families as they move from shock over their loved ones’ murders to advocacy for a hate crime conviction that never materialized.

RELATED: Parking spat as motive for triple murder? N.C. Muslims don’t buy it

Film poster for “36 Seconds: Portrait of a Hate Crime.” (Courtesy image)

The 99-minute documentary, which follows the police investigation and the trial of Craig Hicks, the shooter who confessed to the crimes, was screened in Charlotte, Durham and Cary, North Carolina, as well as at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival in California this month. It will be screened at N.C. State University in Raleigh on Monday (Feb. 19) and has upcoming screenings in Sacramento and Boston in March and April.

The three students all grew up in Raleigh’s thriving middle-class Muslim community, about 25 miles away. They were model students and citizens, volunteering their time with the poor in the U.S. as well as with refugees abroad. Deah Barakat, 23, was studying in UNC’s dental school and had just married Yusor Abu-Salha, 21, who was about to begin dental school. Yusor’s sister, Razan Abu-Salha, 19, was studying architecture at N.C. State University in Raleigh.

On the night of Feb. 10, 2015, an angry neighbor showed up at their door, complaining they had parked in his designated spot (the allegation was proven to be false). He took out a pistol and shot them at close range multiple times — the entire interaction lasting 36 seconds.

He then drove his car to the police department and confessed to the killings, saying he did it out of frustration over a long-simmering parking dispute, a charge the Chapel Hill police investigating the case later repeated in its public statements.

To the families of the slain, the allegation that the murders occurred over a parking dispute was preposterous.

“It’s the biggest thing that I think took away from just healing or just processing it,” Farris Barakat, the younger brother of the slain Deah Barakat, told RNS.

To the families and many others, it was immediately obvious that Hicks was motivated by hatred for their faith. Both Yusor and Rezan, the two sisters, wore the hijab. All three were the children of Arabic-speaking parents who emmigrated from the Middle East.

A scene from “36 Seconds: Portrait of a Hate Crime.” (Image courtesy Full Disclosure Films)

Hicks, an atheist, did not express any Muslim animus specifically, though he had several anti-religious Facebook posts. Witnesses recalled he was unbothered by his white neighbors but began harassing the Barakat couple after Yusor, who wore a headscarf, moved in.

But police investigators never asked Hicks his feelings about Islam or his neighbors’ ethnicity. They had Hicks’ confession and, in any case, North Carolina does not have a hate crime statute that would apply to first-degree murder.

At the trial four years later, Hicks pleaded guilty and was sentenced to three consecutive life sentences without parole. His bias toward his neighbors did emerge in the trial thanks to the work of the assistant district attorney prosecuting the case.

The families were pleased with the trial’s outcome, but they also wanted the federal government to press hate crime charges. Without an acknowledgment that this was a hate crime, they felt threatened, violated and afraid.

That’s when Tarek Albaba, an Arab American with 20 years of experience at Hollywood’s largest studios, stepped up. Albaba grew up in Charlotte and had relatives in Raleigh. Though he did not know the murdered students, he had connections in Raleigh’s Muslim community and said he felt duty-bound to take on a documentary project.

“They are family, and I needed to apply my skills and my training to amplify their voices,” he said in a phone interview from California. He began filming on the one-year anniversary of the murders and traveled back to North Carolina repeatedly over the years, in addition to Washington, D.C., for interviews with Justice Department prosecutors and with a Muslim member of President Obama’s National Security Council, Rumana Ahmed.

His documentary explores the state of hate crimes. Despite a yearslong surge in crimes based on race, ethnicity, religion, gender, disability and sexual orientation, hate crime laws in the U.S. are inconsistent and their application incomplete. Police departments across the country, including in New York City and most cities in California, do not submit information to a national reporting system. The federal judiciary does not always prosecute.

One reason this particular case was not prosecuted is that Hicks already faced the steepest of penalties — three counts of first-degree murder (the district attorney declined to pursue the death penalty).

An added federal investigation would have made the prosecution longer and more burdensome, said Joseph Kennedy, a law professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Plus, it was not clear what added value the federal charges would bring.

“When the feds think about allocating their resources to hate crime prosecutions, they look at, ‘What’s the need? Will we add value here?’” Kennedy said. “When you look at this case, you’ve got a prosecutor’s office totally committed to prosecuting the case and who is not going to downplay the bias aspect of it. And then you’ve got a slam dunk case and you’ve got maximum possible punishments. So, from a practical point of view, the feds may have thought, ‘We’re not going to add anything here. In fact, we might just sort of slow things down and gum things up.’”

That, however, was a tough pill for the bereaved Muslim community to swallow.

“What we want the audience to ask themselves is, if this triple homicide was indeed a hate crime, how many others are slipping through the cracks?” asked Albaba. “Is it 100, 1,000, tens of thousands? We’re talking about an epidemic here that’s not even being addressed.”

Farris Barakat, who now lives in Greenville, South Carolina, said he appreciated the documentary and hopes it shines a light on the need for more aggressive hate crime prosecutions to help people of minority faiths feel safe. He noted that former President Donald Trump running for the presidency is only adding extra anxiety.

“People are afraid, disheartened and feel alienated time and again,” Barakat said. “Calling it a parking dispute further adds to that alienation, to feeling misunderstood. So this is a story that needs to be told.”

RELATED: Two years after slayings, these Muslims show hate cannot overpower love

Source link